Projects

LITTLE BRINKLAND

Following three inhabitants of a fictional neighbourhood in the then-future world of 2012, ‘Little Brinkland’ presented a plausible – if occasionally surreal – future for our working lives. Extrapolating from current trends in economic dis-intermediation, technological developments and demographic shifts, we developed a cluster of challenging, speculative scenarios, layered in space.

Working with Colebrook Bosson Saunders and the Helen Hamlyn Research Centre, we turned a keen designer’s eye to the future of work, generating possible scenarios for products, services and experiences that reflected contemporary trends and emerging technologies.

Our research began with a series of interviews and ‘flickr dialogues’, in which participants posted and annotated images of their workplaces, interests, and obsessions. From this, we began to iterate scenarios of three possible protagonists, developed further in close dialogue with our client.

Alice is a young woman who works from home. She is a cyber-junkie and victim of data-neurosis, for whom the boundaries between love, work, food, sleep and life have all but disappeared. She spends the majority of her waking hours working, living, and socialising inside the world of her screen.

Andrew is a nomadic city worker, network king, aspiring entrepreneur and occasional hacker. He has made the city his workplace and prefers flexible work over a fixed office environment.

Elizabeth is an anxious office worker, a librarian on the verge of retirement. She is eager to discover new work opportunities and learn new skills.

Working with insights from research on emerging technologies and demographic change, we took these three archetypal protagonists, projecting their lives into the near future, and inventing new jobs and roles that would reflect their aspirations, values, and skills.

These images below demonstrate some of our process of ‘job invention’. Though this stage of our research was grounded firmly in industry research and foresight, the cascade of associations, details and feedback loops fed a process that was both creative and organic.

To effectively visualise new ways of working, and the possible products and services that might arise from the combinations of these new jobs, we needed a social and spatial context in which to embed them.

Here, we had the idea of creating a fictional neighbourhood in the city of the future, which we dubbed ‘Little Brinkland‘. This fictional architectural space, a small corner of the then-futuristic world of 2012, allowed us the flexibility to envisage various kinds of work space, visualising jobs, services, products, and human interactions, by deploying multiple scenarios in a detailed city environment.

Working to a near future horizon, the jobs we created for our protagonists were not entirely novel, relying on the creation of entirely new industries or radical, disruptive change. Instead, they resembled strange mutations of existing roles and careers – logical, if unexpected, extrapolations from the then-contemporary workplace.

Assuming the role of a chronicler in the world of Little Brinkland, we were able to narrate the stories of our three protagonists’ lives from an ‘insider’ viewpoint. Producing three short films, we borrowed the language and techniques of the documentary, with diegetic narration and in-depth interviews with the characters.

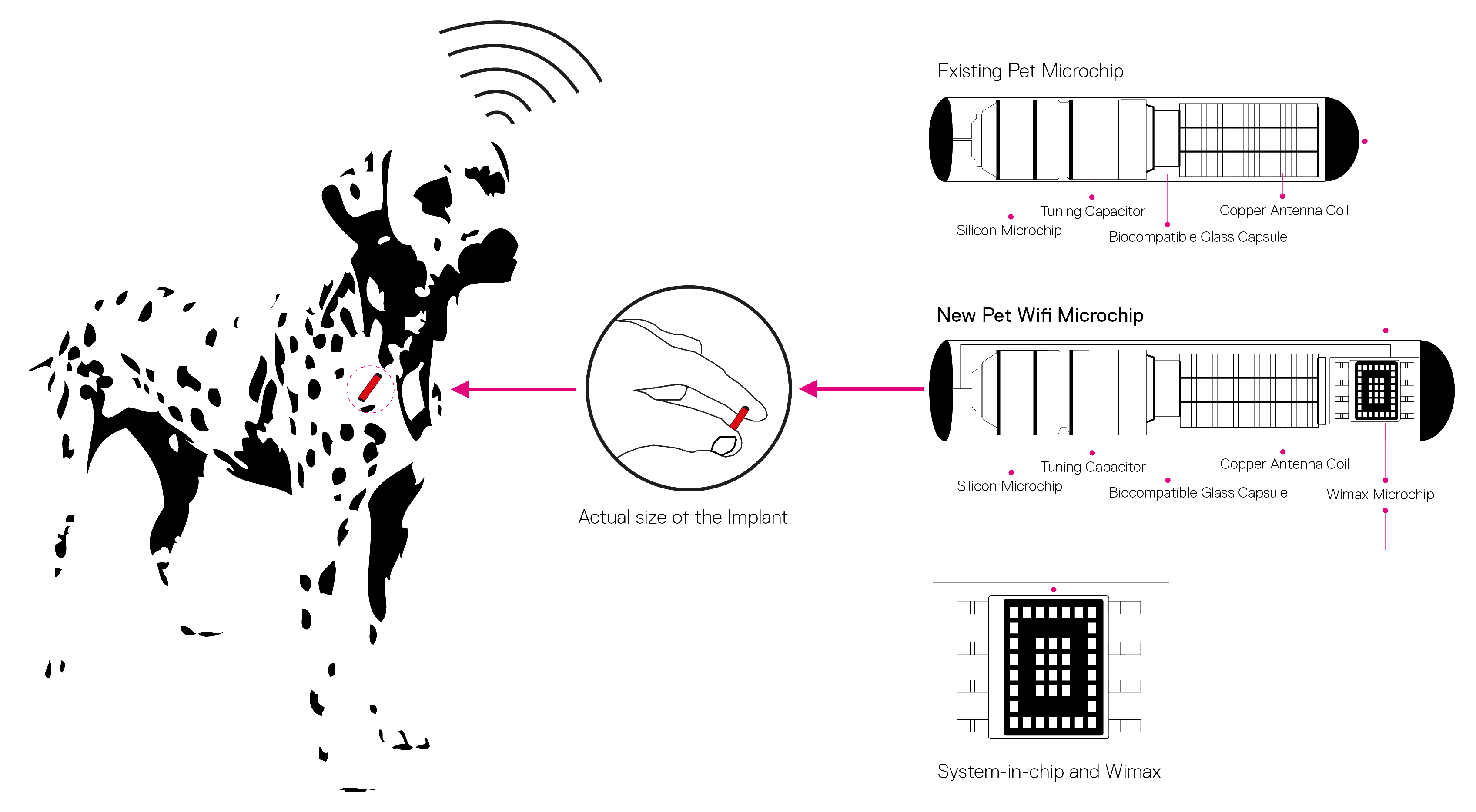

The first character, Andrew, used to be a nomadic city worker, hacker, and aspiring entrepreneur. By 2012, he owns a ‘Pet Implant Consultancy‘ in Little Brinkland, working with his friend Ronny, a veterinary surgeon. This business augments the functionality of real pets, using technologies and techniques demonstrated by Andrew on his own pet dog, Luka.

After all, if we can make our objects tweet, emote, and even monitor our happiness, why not our pets? What possibilities might emerge when we move beyond ‘personalised dog tags’ to a new kind of augmented animal?

Our second protagonist, Alice, used to be a cyber junkie. As a young homeworker (‘avatar supply agent’) struggling with data addiction, she now visits one of the many of the coldzonesin Little Brinkland to work and meet people.

For someone like Alice, who struggled to disconnect from the network, this was an exciting new experience. Coldzones are physical, non-technological, transient spaces in Little Brinkland, where the digitally exhausted Brinklanders can go offline. Through location-specific, unique services coldzones have created new pockets of social exchange and conviviality, free from surveillance and constant tracking – perforations in the urban landscape.

In 2006, Elizabeth was an anxious librarian on the verge of retirement. In Little Brinkland, she has found a new job as the neighbourhood’s Data Archivist. She visits people in their homes, assesing their unique data needs, and advises them on suitable plans and accounts in the newly-opened data bank.

Working from projections, trend reports, and research publications, we adopted an attitude to work that favoured flexibility and multi-skilling over the sedentary single career. In this, Little Brinkland offered a window into a world in which corporations were still driving the economy, but increasing numbers of individuals had chosen to operate outside the traditional ‘corporate office’ environment.

This project became the starting point for our interest in design futurescaping. Since its conclusion, we have continued to develop work on animals and augmentation through LukaLive, which has been featured in MoMA’s Talk to Me exhibition.